How To Resist a Gold Mine

How a small community fought against one of the biggest mining companies in the world

Nestled in the foothills of the Andes in Antioquia, Colombia, lies a network of resistance. Passing through, you may be hard pressed to notice. But the clues are everywhere if you know what to look for: Flags hang over doorways, boldly stating: “NO A LA MINA.” Posters are hung in shop windows with the same message. Beautiful art adorns the streets, bringing to life the spirits of the mountains, of water, of life itself, the message of togetherness and interdependence spelled out in the poetry alongside them. Patterned bracelets, bright in defiance, flash on the wrists of villagers who greet each other, laughing. A stranger could miss all the little clues and remain completely unaware of what the people of this small town have achieved. The guardians of these mountains are keeping at bay the second-largest gold mining company in the world from tearing up their home.

We arrived on January 1st to uproarious celebrations welcoming the New Year. The entire town was out, drinking and dancing and laughing. We wandered past statues dedicated to the town’s founding couple and saw groups of men happily snoring at their tables, flanked by beer bottles. Children chased pigeons and fruit sellers chatted merrily together underneath awnings of some of the largest, most colourful fruit we’ve ever seen. Behind the town church, the mountains rose steeply, majestic and lush in their richness. Forest covered the mountain side, a kaleidoscope of dark greens which would shift with the changing light. The land is so rich and wild that Tamesis and the mountain it nestles into are home to five different ecosystems in a range of just a few thousand metres, each winding into the other, like the threads of rope twisting together with purpose and strength. The resistance movement that webs across the mountain side mirrors those very ecosystems, made in the image of the mountain they are dedicated to protecting, interweaving a complex and thoughtful strategy rooted so deeply in the soil that even in the face of danger these unassuming people refuse to budge. They call it Visión Suroeste.

Robert: The resistance recalled images of my Father’s native Samoa. There people escape the tropical heat of the beaming sun under the wall-less thatched roofs of a fale, weaving baskets and fine mats from the long leaves of coconut trees. Each leaf joins an intricate system of patterns, no more, no less important than the last or the next. Visión Suroeste, much like the fine woven mats of Samoa, showcased a beautiful pattern of individuals, groups and initiatives, delicately combined to form not only a formidable network of resistance, but a powerful collective of custodians, defined not by their stance against, but their love of.

When we set out to make films about what to do for a world in crisis, we expected we would learn how to answer that question by the end of the year. We did not expect to come away with answers immediately, but our two weeks with the people of Visión Suroeste were astounding. They have created a project that impeccably applies theories of change to material reality, creating heartfelt impact for both their neighbours and the mountain itself. The guardians’ strategy acutely targets both the immediate threat of the proposed mine and the wider economic systems that facilitate mass destruction in the name of progress, allowing them to weave baskets of relationships to catch themselves in. This protects them from falling prey to the lies, manipulation and perverse incentives which were expertly wielded by AngloGold Ashanti, the mining company embattled in a long and sustained attack to get access to their land.

At the heart of their strategy, the wellspring from which everything grows, is the concept of “territoria” – territory. It was the very first thing we were taught, wandering out of the town towards the river with two members of the movement. Sebastian is a project leader who identifies as a “neo-peasant”, someone returning to his home village in order to be closer to his territory. Astrid, our guide throughout the two weeks, and one of the most effective and joyous people we have known, returned to have her son 16 years prior. They led us down a winding dirt road, Sebastian translating between Spanish and English, explaining that “territory” is a false translation. Territoria is not about ownership or demarcation, it’s a concept that denotes the aliveness of the land, that speaks to the web of life that makes the land, including the mountain itself and the giant boulders which rise up out of the earth, and all the intangible beauty connected to it, like spirits and ancestors and stories. Territoria reflects the reality of all that is and all that has been, a word that carries in it the very being of a place: living, breathing, deserving.

Rachel: I remember that moment with Astrid and Sebastian. Something moved inside me, like a piece slotting into a puzzle. Territoria made concentric circles of all the living beings, refracting how they overlap to create networks of life. It put the villagers in that network, not above it, and immediately captured how they, too, are dependent on the land. Perhaps the thing I loved most about it was that it was this territoria, right here in Tamesis – not the whole state of Antioquia, or the whole land of Colombia. Being bound by their territoria put limits on how far they could scale – meaning they could reserve their energy for rooting down. I thought of Extinction Rebellion in the UK – the very first protest they did through London, pulling that extraordinary pink boat, put climate change on the map. But would it have been more effective to walk down their own high streets instead?

It is easy to see why the locals want to protect this land: it is alive. Sprawling rivers snake across canyons of lush green, their voices gushing into the crisp, misty air. Floating rivers of clouds glide around us, carrying water between corridors of mountain and valley. Vibrant birds colour the landscape with their bright plumage of lurid reds, yellows and blues. Forest covered mountain ranges reach out to the sky, their sharp peaks dotting the skyline with jagged dips and ascensions of pre-historic rock. Adorning these lateral faces are glittering, cascading waterfalls which pour into the rivers Cauca and Frio whose tributaries reach out with infinite fingers into every part of the ecosystem, a venal system pumping life into the network. Flowers flamboyantly dance in gentle breezes, swaying with the thick foliage, attracting large bees to pollinate their companions. Hummingbirds hover about their nectar with rapid silent wings almost imperceivable to our eyes, and fat plump fruit dangles everywhere from the trees and vines. The richness here is self-evident and intangible.

Robert: At what point did we decide that such ecosystems of pure, innocent beauty could be annihilated and sacrificed in pursuit of the twisting of human society into a homogenous, industrial amalgamation of glass, metal and concrete? Surely no one would argue that this region would be improved by a Starbucks or a casino. Yet there is a willingness to trade regions like this to build ‘developed’ cities thousands of kilometers away. The distance from the scene of the crime perhaps enables our ignorance that wondrous self-maintaining ecosystems are being destroyed to maintain others of overconsumption and frivolity.

Although the town was only founded in 1858, there are eons of history in the soil. Intricate markings etched into boulders show that this mountain was once sacred to the people who lived here before the Spanish arrived. But they had moved on by the time the town was founded, which quickly developed a tradition of agriculture in the rich soils. The farmers have long grown coffee, bananas, avocado, oranges, maracuja, passion fruit and so on. To this day, farmers descend from the mountain side into the town with donkeys to collect supplies for themselves and their neighbours. The town works in that intricate way of living organisms who have developed the processes they need to survive. On one journey to visit Jerico, the next town where the mining company has opened up an office, we saw the bus conductor doubling as a postman, taking packages from people on the side of the road who explained where they needed to go. He would holler for the bus to stop and take the package to the front door, sometimes carrying huge sacks of rice on his shoulders. Three hours from the nearest city, the people of Tamesis have developed the systems they need to live well – and many of those systems are built on faith.

Mining would have a devastating impact on the community. It would pollute the rivers, poison the soil, suck in the youth, create wealth inequality, attract illegal activity and, above all, inhibit their ability to fend for themselves. The mine offers the locals short-term financial gain for long-term poverty, destroying the traditions and histories which give these people their identity and the systems which have organically sprung up between them. And, when the lease was up and the company gone, leaving behind a gaping wound in the mountain, grey rivers and wasted soil, the community would have no territoria to go back to, no local economy to go back to. They would be uprooted in themselves, just like the mountain they defend.

We quickly learned that the mining company was targeting the gold in the bellies of the mountain in the name of the energy transition. This is a tension that land defenders have to face down in resource-rich territories. Like Western activists, these environmentalists also want to see the end of fossil fuels – but they refuse to have it come at the cost of their home. We interviewed farmers, scientists, high school students, agro-ecological innovators, youth leaders, indigenous defenders and even a Catholic nun. Each person a thread adding their own touches of colour and elements of light to this plural network. Their chorus rang clear: Not here.

The defence movement of Visión Suroeste is keenly aware that the wealth dug out of the mountains they protect will not stay with them. It won’t even stay in Colombia, they told us, explaining that the energy transition is yet another manifestation of extractivism and neocolonialism. Why should the global north go green at their expense? And why should they believe that green energy will be inherently positive if it’s sourced with the same violence as fossil fuels?

Rachel: I felt relieved having this conversation over and over again. I’ve long questioned the dominant narrative of simply switching to renewable energy as if that will solve all our problems, and many people disagree with my stance. Renewables are a huge driver of tension in the eco-movement, and for all the talk of “just transitions”, there’s been very little evidence of it in the real world. The reality is industries are unlikely to change what works for them while their incentive is still to protect the bottom line. There’s also an inherent anthropomorphism of justice if it discludes the right for Territoria to have her own voice. Even if all the human beings of a place agree for it to be sold off to industry to be chopped up and drilled into and dug up – would the other species agree? What consent can the voiceless give? I don’t dispute that we need a different energy source, but surely a just world will never involve one group making unilateral decisions which destroy the web of life? When we humans do that to other humans, it is called genocide.

Sadly, attacks on territoria like Tamesis are not isolated. Most mining now targets the materials needed for renewable energy infrastructure, and many of these mines overlap with designated Protected Areas and Remaining Wilderness areas. These locations also contain a greater density of mines than mining activity which targets different kinds of materials. Studies have shown that mining for renewable energy infrastructure will exacerbate threats to the planet’s remaining biodiversity, and that these threats could even surpass those averted by climate change mitigation.

The world’s biosphere is severely depleted by our industrial action, and many remaining ecosystems are threatened by green industry. The people of Visión Suroeste are doing what they can to protect their territory but we are all interdependent beings in the great web of life that is planet earth. We are all home to one territoria, even if we cannot defend it all at once. To do so, we need to come together and take responsibility for where we are, and grow our roots deep in the soil to reach out to one another and stimulate the life that once teemed beneath the surface. If we don’t, we will never keep at bay the corporate multinationals which fail to see value in the intangible. And once they get their claws in, there is no end to the destruction they are willing to wreak to get their hands on what they want – as we saw firsthand.

Mining — A Harsh Reality

Towards the end of our two weeks with the Visión Suroeste team, we got wind of a neighbouring town which had been taken over by a multinational mining company some years ago. We immediately told our guide, Astrid, that we needed to see it, to capture firsthand the impacts mining has on this lush landscape. It took some organisation. We needed a local who would be willing to drive us in and out, and a local translator, as Astrid’s 16-year-old son had been our Spanish interlocutor, and his father thought it too dangerous to go with us. In the end, we couldn’t find a translator. We went anyway.

The winding drive into the town descended a large mountain side, hugging the ridge wall. The landscape slowly transformed from the usual green scenery into the set of a Hollywood dystopian film. Berths of narrow mining veins started appearing in the sharp inclines decorated by corporate signage and flowing grey water. The prevalence of litter as we neared the town increased exponentially as piles of garbage became commonplace amongst haphazard shacks built around bores in the earth.

Caught, outside the entrance to a large mining tunnel, between two convoys of trucks, we stuck our cameras towards the windows to film the chaos and dust. Our driver urged us to put them away. We had caught the miners’ attention and suspicion was quickly becoming outrage. The mine dominates the locals’ economy and tensions run high, any threat to the mine understandably perceived as threats to their livelihood. They have no other options here. The mine has utterly destroyed any possibility of farming or tourism. Even those who refuse to work for the company still mine the mountain, excavating the soil beneath their living room floors to access the minerals underneath. We were told the military has been deployed repeatedly throughout the last decade at the behest of the corporation to either incorporate their sites or shut them down, leading to violent clashes with the locals.

Rachel: This is the great sickness at the heart of capitalism, the swiftness with which neighbours are forced to turn on each other to protect the very thing that has driven them apart. By destroying all other local economic possibilities, the company miners became its own private army, guarding, for a small wage, what had once belonged to all of them. People died. The body of the town’s priest was found just days after protesting against the local church being sold off to make room for the mine. He had said in a Youtube video posted four days before his death: “If they are going to drive me out from here… They will have to expel me by way of bullets of machete.”

Only a single gravel road exists in and out of Marmato, providing barely enough room for busy trucks to pass each other. Often we had to wait for large convoys of as many as 10 trucks to reverse the road, bastioned between the mountain side and a steep cliff, to make way for an incoming convoy of yet more vehicles. Each vehicle was forced to find a nook between shacks to sandwich into, tip-toeing the sharp drop. In amongst these heavy vehicles, motorbikes and processions of mules, loaded with long logs, wound through the disarray. Above us, networks of ropes and pulleys moving buckets of ore up and down the incline, and below our feet, networks of tracks that allowed carts to spew out of incisions in the rock face. We saw children as young as 12 equipped with harnesses and head torches, others working the machinery on the surface level.

The pockets of dust-covered miners became a sea as we approached the town. Our driver explained that we were heading towards what was now considered the main square, as the original one had been destroyed: The company had moved the town further down the mountain in order to expand its mine. We were shocked, and asked him to repeat. But we had heard right: The company had cut right through what had once been the historic centre of this 600-year-old settlement. The only piece of history left standing was a portion of the old town wall opposite an enormous wound in the earth covered in giant scaffolding and enormous drilling equipment. Giant vats filled with filthy water stood as monuments to the Green Transition’s conquering of the region’s gold. A 30-metre wide crevice extended from the former town so that water from the Cauca river, once grey with cleaning the ore, could be expelled back downstream.

Just a few decades ago, Marmato was a very different place. The town is a historical mining hub whose 600-year old practice of small scale, artisanal mining was transformed when a series of large mining corporations came knocking at their doors. A brief period of corporate extraction existed from 1908 until 1925 when the mine was expropriated and closed. The locals went back to their tradition of artisanal mining until another set of corporations began open shaft mining in 1993. The current iteration of the project is owned by a Canadian company, Aris Mining, who took over in 2012. They project that the mine, over 315,000 metres at its deepest, will generate $74 million over its estimated 20-year life span.

The question of scale emerged as we descended into the town, a question which had become the theme of our investigation. What effects had artisinal mining had on the mountain and its ecosystems? Was the tradition of mining justified when it was small? It’s impossible to quantify without scientific investigation but what is certain is that the wealth in the bowels of the mountain was drawn out — and would have continued to be drawn out — over generations of miners, supporting entire family lineages. Yes, there would have still been destruction, but destruction over such a long period of time that some of its impacts would have been mitigated: less water used in a lifetime, less tunnels dug, less soil weakened. Excavating the entire mountain in 20 years gives the local ecosystems no time to recover and heal themselves. The wound, rather than scabbing over in places every day, just deepens.

Our driver dropped us off in what we were surprised to learn was the main square of Marmato. Nestled next to a busy thoroughfare of trucks and mules, encased in clouds of dust, we had coffee, and waited for our interviewees. Opposite our table was a large mural reminiscent of industrial era propaganda posters depicting a miner with a superhero physique crawling into a mine shaft, a majestic eagle flying above and a catholic monk nursing a bible and a child, set against healthy trees and a large green hill. The reality could not have been more different. Less than 30 metres from what should have been the beating heart of the town stood several mine shafts, a collection of massive lorries, and a string of crowded mules being watered on a thin, meagre steam of cloudy putrid water.

Robert: In the foyer of the local Ex-Service’s Club in the small historical coal mining town I grew up in in Australia, there is a life-size diorama depicting a coal miner. His arms are mechanised so that he can pivot between raising a pickaxe above his head and striking it against the tunnel wall. Pro-mining imagery is commonplace in pubs and park monuments there. Growing up in this environment I expected, perhaps arrogantly, to be somewhat prepared for Marmato. I was wrong. Even Australia, with its flagrant environmental abuses, would never today allow people’s lives to be so intimately affected. Its citizens, as members of the global north, would never be swallowed so wholly by this type of violence. There is always somewhere to escape the noise and pollution. The residents of Marmato don’t have an escape.

We remarked on the lack of non-mining infrastructure in the town. If you did not work in one of the few drug stores or food shops, you worked in the mine, or you sold tools to the miners, or you herded equine for mining transportation. The dust from the mine choked the entire town and the white noise of machinery was relentless. It was hotter than anywhere else we had visited on account of the reduced greenery, constant vehicles and humming instruments. We watched as a woman swept clouds of dust from her restaurant into the square and we realised the shadow of this mine touched everything. People, homes, the environment, employment, buildings, even food had been swallowed up. The inescapable pollution, the piles of rubbish, the watchful eyes of the locals, the lack of nature, the unbearable heat, the incessant noise, the animal exploitation, all of it combining into a melting pot of discomfort and urgency to leave.

Rachel: Being there was exhausting. I worried constantly about the dust lining our lungs, and shuddered at the long mistrustful looks cast our way. It couldn’t have been a starker contrast to Tamesis. The land was simply dead: gouged open, turned inside out. There was obviously no possibility of growing anything here, and the water looked outright poisonous. And the townspeople treated the land as if it were dead, leaving mounds of putrefying rubbish in the street. My heart ached every time we saw a child wandering through this noisy, chaotic, dangerous wasteland. Already, there are stories of the townspeople having increased rates of disease and sickness. “They look different", Astrid had said before we went. And they did.

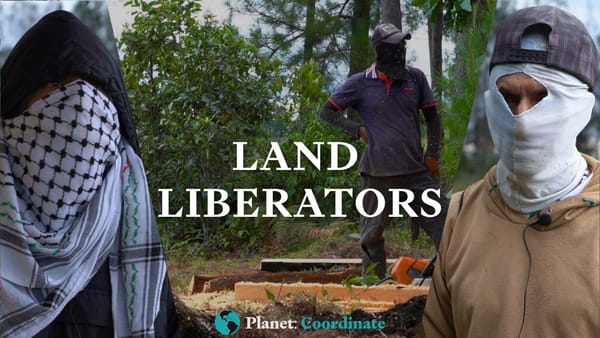

The leader of the environmental defence for Marmato joined us at the cafe. He was lively and welcoming, and sprang out of his chair to walk us to a spot where we could do the interview away from prying eyes. We settled on an abandoned basketball court, choked by weeds, accessed through a hole in mesh wire. Before long, a woman joined us, steely with anxiety. These defence leaders risk their lives to protest the mine, and before putting their faces in front of our camera they wanted assurances that we were on their side. Slowly, using google translate, we chipped away at their hesitation, explaining our politics and values. The woman looked deeply into us and something was transmitted. She agreed.

As we conducted the interviews, five dishevelled children entered the court. We watched in horror as these kids, the oldest couldn’t have been more than 7, began playing with the piles of rubbish scattered around the court by pigeons and chickens. They sat amongst piles of waste, exchanging trinkets of discarded food cans and kicking around plastic. Instead of being objects of disgust, this refuse provided an opportunity for finding novel playthings. They picked up their new treasures and chased each other around the wire fence and up and down a set of concrete steps.

Robert: It was shocking to watch how desensitised these children were to waste. I recalled the public basketball courts in Tamesis, teeming with laughter and bicycles making concentric loops around friendly games. It was a jarring comparison. As we neared Marmato my first observation was the increasing prevalence of trash. It was obvious that as time went on and their home had been more and more extracted from, so too had it been increasingly disrespected. It was not just the physical landscape that had been transformed. People’s attitudes and minds towards the land had calcified. If I lived amongst choking air and grey rivers and a pillaged mountain, would I care about throwing my trash on the street?

The poverty was cloying. Aris Mining, whose slogan, ironically enough, is expanding for tomorrow, has obviously shown little interest in the town beyond what it can take from the mountain. One day, they will finish bleeding Marmato for minerals and leave, having destroyed the region in the process, providing nothing for the locals to show other than a displaced town and a gutted mountain. Marmato was a giant scar of human inflicted trauma on the landscape of the region, and it provided more than ample perspective for why the defence movement in Tamesis had joined up with their neighbours in Jerico to fight back against mining in their territoria.

It was the first time the defence movements of Tamesis and Marmato had met in person. Astrid wept openly as the Marmato defenders spoke of their territoria, what it had once been, its beauty, its life. This town had once belonged to the villagers. There had once been something here other than dust and heat. The territory had been swallowed by a beast and sat in its belly, disintegrating slowly, its ecosystems turning to ash in the mouths of those who loved it.

We watched from a distance, moved by their solidarity and care. When we left a few hours later, having been guided around the town, we were presented with a small gift: a small piece of ore and miniature carving of a sifting bowl, both dusted with gold. We shook the hands of these brave leaders and thanked them profusely. Then, we were back in the car, grateful to be leaving the dust and the heat, sad for those we had to leave behind.

These defenders were once ordinary people, forced towards bravery because the only other option was defeat. They risk their lives so that their bodies may stand at the foot of these mountains and be one remaining barrier to the power that looms above them, threatening to swallow them whole. Often, heroes don’t have the time to undertake the great odysseys favoured by the Greeks. They can be made in a moment, when they face down the barrel of inevitability and say: Not here. Not today. Even as that beast bears down on them, they remain, repeating: Not here. Not today. The Marmato defence movement are caught in the very belly of the beast and still they say: Not here. Not today.

The beast, in all its arrogance, smirks: If not me, then what?

The defence movement in Tamesis has an answer.

How To Confront The Beast

When the mining company, AngloGold Ashanti, arrived in Antioquia over a decade ago, they needed access to the land to establish whether or not a mine was viable. Their strategy was the same as many destructive industries all over the world: they lied.

They set their sights on Jericó, the neighbouring town to Tamesis, and approached local farmers under the guise of pretending to be an agricultural initiative. They pretended that they could help the farmers increase the health of the soil and improve the agricultural practices. The farmers, believing them, agreed for the company to begin testing their land.

It took some time, but once word got out that the strangers were testing for minerals in the soil, the farmers rescinded their invitation. The company came anyway. So the farmers organised quickly, using their own bodies to block the company’s access to roads. These stand-offs went on for years. The farmers protested weekly, blocking the company’s access and spreading word through the town. They set up a local newspaper to warn of the company’s action and encourage support for their movement. They insisted that Jericó has always been, and should remain, an agricultural zone, and that mining would destroy the traditions and social relationships in the town.

But the company didn’t back off, instead enlisting Colombia’s special police force who, we were told, had been instructed that the farmers were illegally blocking the company from their own land. This was a lie. The farmers would explain to the police force every time what had actually happened, forcing the company to enlist different squads who had no idea of the truth.

Sometimes the company would deposit machinery necessary to test and drill, leaving it overnight begin digging up the land the following day. The farmers enlisted the help of former employees who had left once finding out the truth to dismantle the machines overnight. These employees are now fighting lawsuits filed against them.

The company changed their strategy after their cover was blown. They continued employing locals and told them that they needed the mine, that they were under-developed and poor, and that only through this vast multinational project could they see a decent quality of life. This is laughable. Jericó is quaint and content, rich in tradition and history. But the lies started to seep in. AngloGold Ashanti understood the power in controlling the narrative and families were driven apart. Some people wanted the mine and all the promised benefits, others continued to warn against its devastating impact.

Robert: Throughout our time in Antioquia it became clear that this trend of dominating narrative and manipulating language was a consistent form of violence. “We are coming to realise how we are colonised, even from the language” mused one of our guides. Towns named after European settlements, Milan, Venice, even Tamesis named for the Thames in England, are dotted throughout Colombian maps. Christian symbols were intentionally placed on indigenous sacred sites. The first murals painted in these towns were of European landmarks. As if to say, Europe is what you should strive to be like, Europe is what is worth protecting. These forms of violence infect people’s minds and soften them to the idea of sacrificing what they do have for a concept of what they might have.

AngloGold Ashanti set up shop in Jericó under a different name, their slogan boasting their proud contribution to the energy transition. They continued to face-off against the farmers every week. The protests began, and remain, in the spirit of non-violence. But these 200-odd farmers could not hold off the fight by themselves. They joined forces with other land defenders, including the concerned citizens of Tamesis who knew their territoria was on the chopping block, too. They diversified their tactics, getting local defenders elected to small positions of authority, such as legal representatives of the local aquaducts. Swiftly, the movement grew to include farmers, indigenous defenders, youth, residents and even politics, with Gustavo Petro, Colombia’s first left-wing President in decades, visiting Jericó and offering support.

Rachel: We contacted President Petro’s office upon learning that, asking for an interview. To our amazement, we got a response, promising that if a slot opened up we would be able to speak with the President. Whether or not this happens, it was a small but infinite gesture of a different kind of politics: One that makes time for independent initiatives, respecting the networks we weave together that offer an alternative to a world dominated by centralised power.

But something happened. After over a decade of fighting, people started to burn out. They were running out of energy to fight a beast which had infinitely more resources than them. They couldn’t see beyond the fight. They didn’t have much more to give.

They realised that, to go up against the beast — which they define as multinational capitalist forces — they needed beauty.

We interviewed Kata, one of the cofounders of Visión Suroeste, a Colombian filmmaker based mostly in Paris. She has a beautiful story about how she came to be part of the movement operating out of her hometown after making a film in the region. The locals reached out to her and asked for her help building the narratives they needed to win this war and she immediately agreed. After a few years, her body was on the brink of breakdown. She told us a story of when, in utter exhaustion, she could do nothing but lie and listen to the birds outside her window. It was then that the idea of beauty came to her, and Visión Suroeste developed a new strategy.

They began to weave love into everything they do. They realised that they could not hold off this company forever — they needed more people to resist with them, and to do so, they needed to show why.

Astrid launched an annual music and arts festival on the bank of the River Frio, showcasing the wonders of the mountain and the vibrant necessity of the river which gives them all life. Her husband wrote songs to the mountain, music of love and promise, dedicated to the magic of their territoria. Their son, Maxi, is a key member of The Pollinators, a youth-led science group which takes groups birdwatching and teaches younger children about the many species hidden in the land. The Pollinators often team up with a participatory science group launched by the team at Visión Suroeste, whereby locals learn how to observe and collect data on the nature they protect, led by volunteer scientists and in collaboration with nearby universities.

Alongside this, a co-working cafe, Casa Solar, was launched promoting indigenous art, symbols of resistance, and other traditional crafts, so that the indigenous defenders have a marketplace for the beaded bracelets they make in resistance against the mine. Maxi’s grandmother runs the cafe, and it’s where the Visión Suroeste team meet to organise themselves. They are committed to spreading the word online, showcasing the beauty of the mountains they have promised to defend.

They have also organised interdisciplinary teams to help educate and transition local farmers away from monoculture plantations, instead planting agro-ecological plots of their main product, supported by many other plant species which promote local biodiversity. Understanding that transitioning represents an up-front cost for farmers, the co-working cafe offers a marketplace where the farmers can sell their goods for a higher price, sharing that cost out between community members. In a similar vein, another cafe was launched with help from a Colombian NGO that only sells agroecological coffee produced by local farmers, creating a collective of 12 previously separate and independent farms who now work together to provide the high quality beans. There are many other initiatives to help local farmers transition their cocoa plantations, teaching the locals how to make cacao nibs and other chocolate products. The team also works with the original defence movement who have been guarding this land for decades, deepening plans for water security in the region.

Robert: It may be controversial to say, but I have sympathy for miners the world over who resist the closure of their workplaces. In my home town in Australia, decent, hardworking, caring people vehemently support and work in coal mines. They have never been show another way of living, they are not fully aware of the impacts of fossil fuels, and their concerns are not alleviated. Rarely are they offered a feasible path for what happens after they lose their livelihoods. But we have more in common with these people than we do not. Most people just want to support their families. Surely, that is something we can sympathise with and use as a mutually shared platform to bridge the gap between our values and restructure the cultural and psychological walls that implicitly exist in our society. The people of Vision Suroeste have found a way to do this. They offer monoculturists a reason to abandon destructive practices and a way of transitioning to sustainable livelihoods. They have found a way to incorporate and welcome, rather than vilify those they have differences with. Therein lies, I think, the key to building a better world.

One of Visión Suroeste’s core beliefs is that to love a thing you must know it. Rather than demand support from a position of moral authority, they have worked diligently to invite their neighbours into a learning process in the hope that by building awareness of how teeming with life their territoria is, others will join the call to protect it. This is a strategy which promotes deepening each person’s relationship to the land, and generating new relationships between each other with smart economic decisions, which both strengthen and diversify the root networks that keep the soil of their home intact. They work from the premise that love is a better motivator than fear or righteousness.

This means their approach is always multi-pronged. They listen first, finding out what people need, what they lack, and then devise a strategy for that need to be filled by the local community in a way that also promotes the land’s health. They understand that people cannot be asked to sacrifice their livelihoods, and that if they can build a solid and interdependent local economy then their neighbours will be able to resist the mine for much longer. They understand that learning is tactile and progress material, that the impacts must be tangible and localised to their territoria. With every action, they are weaving together new relationships between people, nature and politics, showing how to gain freedom and independence rather than demanding those concerns be sacrificed temporarily for a greater goal. There is no greater goal, because for the people of Tamesis and Jericó, theis security lies in the integrity of the web of life that surrounds them. They are part of the mountain. They need to defend it as much as it needs their defence.

Rachel: I have always been suspicious of when people talk about the importance of highlighting economic value when promoting “solutions”, convinced doing so only promotes financialisation and entrenches a dangerous narrative that economics is the priority. I still think that on a national and international level, but Vision Suoreste showed me that what happens and is said at the ground level is very different. When the locals talk about economics, they’re talking about the mechanism of their survival, not politics or theory. The market, to them, is not the FTSE or an invisible hand, it’s the town square and the wider network of relationships that support each other to exist. Suddenly, the niggling question of scale clicked into place: Things lose their form when expanded into ideological constructs which blanket nations and discussion, bludgeoning idiosyncrasies into homogenous masses. It is impossible for a national economic strategy to reflect the idiosyncrasies of locality, or make space for them to flourish of their own accord — unless it decentralises. But decentralising threatens power, and so each node of economic activity is valued by a single metric — wealth — and subject to a singular strategy of external investment. This doesn’t help people build relationships between themselves or figure out how to care for each other. It creates a job market, selling off basic human needs to corporate entities who share the same unilateral approach of provisioning (poorly) rather than facilitating. In the territoria of Visión Suroeste, politics does not mandate their decisions, it reflects the reality of their decisions, creating a diverse and meaningful network of people figuring out how to take care of one another in order to take care of themselves.

Visión Suroeste have woven a network of resistance bound by their territoria which prioritises strength in diversity and binds itself to a location. This binding is not an inhibitor but a multiplier. By not spreading themselves too thin, they have ensured that every action they take reinforces the overall ecosystem of their relationships with each other and the mountain. This is the strength of decentralisation. The amount of good they can do at scale is enormous, fending off one of the biggest mining companies in the world and rewiring their local economy. And this is all possible because they know each other.

Robert: I asked an agroecological farmer how he prevented crops from being eaten if he didn’t use pesticides. He said some of his vegetables were mostly consumed by insects but that was okay. The diversity in life he and his partner had cultivated created a diverse ecosystem where some plants attracted certain insects, and those insects ate other insects. Some plants were for him, and some plants were for them. They had intricately weaved one of these networks of resistance in their backyard. Their scale was small, but it was bolstered by the other small networks woven around them.

Human beings are a caring species. We don’t readily and easily cause harm to those we know. That’s why destructive industries hire strangers to cut down forests and gouge open the earth, why the national guard is sent in instead of local police force, why, in some European countries, ticket inspectors have to travel across the country to do their job meting out heavy fines. We love what we know, and we don’t like to harm what we love. Or, on an even more basic level, we don’t want to be shamed by our community for being an arsehole by fining our friend’s child’s schoolteacher when he forgets his wallet on the tram. These relationships diminish the amount of harm we can do to one another. Stripping them away unleashes the capacity for hurt.

Care flows through the ties that bind us. Small-scale communities have many more ties than single streets in cities because they are interdependent and know one another. WE were confronted with the thought that perhaps effective action can only happen at a small scale, that scaling up will always sacrifice the intimate knowledge from which love springs forth. The conversations we had between ourselves, back in our small cabin after long days filming, centred around this theme. Decentralisation is the only way. Imagine if Colombia was filled with alternatives like these, and they were all connected to each other, like an ecosystem of resistance — imagine how difficult it would be to uproot them.

Rachel: There is a paradox of “the chains of freedom” which speaks to the responsibility we bear when making choices. I began to see that paradox in a new way, not as chains but as roots. Freedom for the people of Tamesis and Jericó is not succumbing to a multinational, preserving the wildness of the mountain and protecting their economic autonomy. Freedom means guarding the opportunity to say no, it means digging down and reaching out. It is intimately connected to the land they love; their territoria is their freedom, and they are bound to it. Freedom is interdependence, not independence.

What does resistance look like? Resistance is not merely an oppositional force. And thank god it isn’t, because we are not equal to the states and companies which seek to squeeze everything we have to give. The most important work of resistance happens underground, when we develop the root networks between ourselves that hold the ground steady when power tries to pull us out. Resistance is planting seeds and watering shoots and working with the teeming power of life itself all around us. Resistance is listening to what people need. Resistance is making space so others have somewhere to retreat. Resistance is placing ourselves at the bottom of the mountain and learning the miracles which burrow and fly and wind over every inch of its height. Resistance is learning that we cannot sacrifice the intangible to protect the tangible. Resistance is refusing to speak for, but speaking with. Resistance is refracting in the light, blinding those who come with their bludgeons and hammers. Resistance is rooting down and reaching out.

Resistance is beautiful.

Our film on Visión Suroeste will be out later this year. Please be patient as we try to pull everything off — there’s only two of us. We’re running this documentary project, the Planet: Critical podcast, and Rachel is writing a book. Your support means everything when we’re in the thick of it like this.

If you know of a movement which would be perfect for this project, please fill out this form.