Mining: A Harsh Reality

Visión Suroeste: Part two of three

Towards the end of our two weeks with the Visión Suroeste team, we got wind of a neighbouring town which had been taken over by a multinational mining company some years ago. We immediately told our guide, Astrid, that we needed to see it, to capture firsthand the impacts mining has on this lush landscape. It took some organisation. We needed a local who would be willing to drive us in and out, and a local translator, as Astrid’s 16-year-old son had been our Spanish interlocutor, and his father thought it too dangerous to go with us. In the end, we couldn’t find a translator. We went anyway.

The winding drive into the town descended a large mountain side, hugging the ridge wall. The landscape slowly transformed from the usual green scenery into the set of a Hollywood dystopian film. Berths of narrow mining veins started appearing in the sharp inclines decorated by corporate signage and flowing grey water. The prevalence of litter as we neared the town increased exponentially as piles of garbage became commonplace amongst haphazard shacks built around bores in the earth.

Caught, outside the entrance to a large mining tunnel, between two convoys of trucks, we stuck our cameras towards the windows to film the chaos and dust. Our driver urged us to put them away. We had caught the miners’ attention and suspicion was quickly becoming outrage. The mine dominates the locals’ economy and tensions run high, any threat to the mine understandably perceived as threats to their livelihood. They have no other options here. The mine has utterly destroyed any possibility of farming or tourism. Even those who refuse to work for the company still mine the mountain, excavating the soil beneath their living room floors to access the minerals underneath. We were told the military has been deployed repeatedly throughout the last decade at the behest of the corporation to either incorporate their sites or shut them down, leading to violent clashes with the locals.

Rachel: This is the great sickness at the heart of capitalism, the swiftness with which neighbours are forced to turn on each other to protect the very thing that has driven them apart. By destroying all other local economic possibilities, the company miners became its own private army, guarding, for a small wage, what had once belonged to all of them. People died. The body of the town’s priest was found just days after protesting against the local church being sold off to make room for the mine. He had said in a Youtube video posted four days before his death: “If they are going to drive me out from here… They will have to expel me by way of bullets of machete.”

Only a single gravel road exists in and out of Marmato, providing barely enough room for busy trucks to pass each other. Often we had to wait for large convoys of as many as 10 trucks to reverse the road, bastioned between the mountain side and a steep cliff, to make way for an incoming convoy of yet more vehicles. Each vehicle was forced to find a nook between shacks to sandwich into, tip-toeing the sharp drop. In amongst these heavy vehicles, motorbikes and processions of mules, loaded with long logs, wound through the disarray. Above us, networks of ropes and pulleys moving buckets of ore up and down the incline, and below our feet, networks of tracks that allowed carts to spew out of incisions in the rock face. We saw children as young as 12 equipped with harnesses and head torches, others working the machinery on the surface level.

The pockets of dust-covered miners became a sea as we approached the town. Our driver explained that we were heading towards what was now considered the main square, as the original one had been destroyed: The company had moved the town further down the mountain in order to expand its mine. We were shocked, and asked him to repeat. But we had heard right: The company had cut right through what had once been the historic centre of this 600-year-old settlement. The only piece of history left standing was a portion of the old town wall opposite an enormous wound in the earth covered in giant scaffolding and enormous drilling equipment. Giant vats filled with filthy water stood as monuments to the Green Transition’s conquering of the region’s gold. A 30-metre wide crevice extended from the former town so that water from the Cauca river, once grey with cleaning the ore, could be expelled back downstream.

Just a few decades ago, Marmato was a very different place. The town is a historical mining hub whose 600-year old practice of small scale, artisanal mining was transformed when a series of large mining corporations came knocking at their doors. A brief period of corporate extraction existed from 1908 until 1925 when the mine was expropriated and closed. The locals went back to their tradition of artisanal mining until another set of corporations began open shaft mining in 1993. The current iteration of the project is owned by a Canadian company, Aris Mining, who took over in 2012. They project that the mine, over 315,000 metres at its deepest, will generate $74 million over its estimated 20-year life span.

The question of scale emerged as we descended into the town, a question which had become the theme of our investigation. What effects had artisinal mining had on the mountain and its ecosystems? Was the tradition of mining justified when it was small? It’s impossible to quantify without scientific investigation but what is certain is that the wealth in the bowels of the mountain was drawn out — and would have continued to be drawn out — over generations of miners, supporting entire family lineages. Yes, there would have still been destruction, but destruction over such a long period of time that some of its impacts would have been mitigated: less water used in a lifetime, less tunnels dug, less soil weakened. Excavating the entire mountain in 20 years gives the local ecosystems no time to recover and heal themselves. The wound, rather than scabbing over in places every day, just deepens.

Our driver dropped us off in what we were surprised to learn was the main square of Marmato. Nestled next to a busy thoroughfare of trucks and mules, encased in clouds of dust, we had coffee, and waited for our interviewees. Opposite our table was a large mural reminiscent of industrial era propaganda posters depicting a miner with a superhero physique crawling into a mine shaft, a majestic eagle flying above and a catholic monk nursing a bible and a child, set against healthy trees and a large green hill. The reality could not have been more different. Less than 30 metres from what should have been the beating heart of the town stood several mine shafts, a collection of massive lorries, and a string of crowded mules being watered on a thin, meagre steam of cloudy putrid water.

Robert: In the foyer of the local Ex-Service’s Club in the small historical coal mining town I grew up in in Australia, there is a life-size diorama depicting a coal miner. His arms are mechanised so that he can pivot between raising a pickaxe above his head and striking it against the tunnel wall. Pro-mining imagery is commonplace in pubs and park monuments there. Growing up in this environment I expected, perhaps arrogantly, to be somewhat prepared for Marmato. I was wrong. Even Australia, with its flagrant environmental abuses, would never today allow people’s lives to be so intimately affected. Its citizens, as members of the global north, would never be swallowed so wholly by this type of violence. There is always somewhere to escape the noise and pollution. The residents of Marmato don’t have an escape.

We remarked on the lack of non-mining infrastructure in the town. If you did not work in one of the few drug stores or food shops, you worked in the mine, or you sold tools to the miners, or you herded equine for mining transportation. The dust from the mine choked the entire town and the white noise of machinery was relentless. It was hotter than anywhere else we had visited on account of the reduced greenery, constant vehicles and humming instruments. We watched as a woman swept clouds of dust from her restaurant into the square and we realised the shadow of this mine touched everything. People, homes, the environment, employment, buildings, even food had been swallowed up. The inescapable pollution, the piles of rubbish, the watchful eyes of the locals, the lack of nature, the unbearable heat, the incessant noise, the animal exploitation, all of it combining into a melting pot of discomfort and urgency to leave.

Rachel: Being there was exhausting. I worried constantly about the dust lining our lungs, and shuddered at the long mistrustful looks cast our way. It couldn’t have been a starker contrast to Tamesis. The land was simply dead: gouged open, turned inside out. There was obviously no possibility of growing anything here, and the water looked outright poisonous. And the townspeople treated the land as if it were dead, leaving mounds of putrefying rubbish in the street. My heart ached every time we saw a child wandering through this noisy, chaotic, dangerous wasteland. Already, there are stories of the townspeople having increased rates of disease and sickness. “They look different", Astrid had said before we went. And they did.

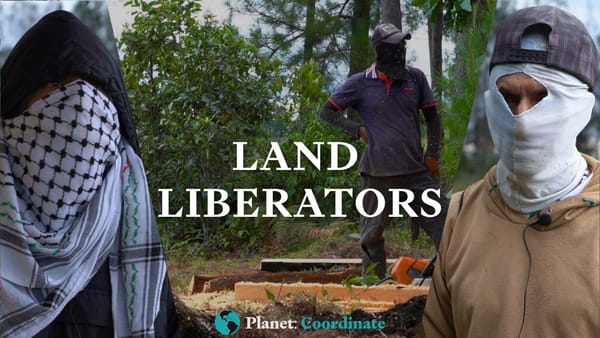

The leader of the environmental defence for Marmato joined us at the cafe. He was lively and welcoming, and sprang out of his chair to walk us to a spot where we could do the interview away from prying eyes. We settled on an abandoned basketball court, choked by weeds, accessed through a hole in mesh wire. Before long, a woman joined us, steely with anxiety. These defence leaders risk their lives to protest the mine, and before putting their faces in front of our camera they wanted assurances that we were on their side. Slowly, using google translate, we chipped away at their hesitation, explaining our politics and values. The woman looked deeply into us and something was transmitted. She agreed.

As we conducted the interviews, five dishevelled children entered the court. We watched in horror as these kids, the oldest couldn’t have been more than 7, began playing with the piles of rubbish scattered around the court by pigeons and chickens. They sat amongst piles of waste, exchanging trinkets of discarded food cans and kicking around plastic. Instead of being objects of disgust, this refuse provided an opportunity for finding novel playthings. They picked up their new treasures and chased each other around the wire fence and up and down a set of concrete steps.

Robert: It was shocking to watch how desensitised these children were to waste. I recalled the public basketball courts in Tamesis, teeming with laughter and bicycles making concentric loops around friendly games. It was a jarring comparison. As we neared Marmato my first observation was the increasing prevalence of trash. It was obvious that as time went on and their home had been more and more extracted from, so too had it been increasingly disrespected. It was not just the physical landscape that had been transformed. People’s attitudes and minds towards the land had calcified. If I lived amongst choking air and grey rivers and a pillaged mountain, would I care about throwing my trash on the street?

The poverty was cloying. Aris Mining, whose slogan, ironically enough, is expanding for tomorrow, has obviously shown little interest in the town beyond what it can take from the mountain. One day, they will finish bleeding Marmato for minerals and leave, having destroyed the region in the process, providing nothing for the locals to show other than a displaced town and a gutted mountain. Marmato was a giant scar of human inflicted trauma on the landscape of the region, and it provided more than ample perspective for why the defence movement in Tamesis had joined up with their neighbours in Jerico to fight back against mining in their territoria.

It was the first time the defence movements of Tamesis and Marmato had met in person. Astrid wept openly as the Marmato defenders spoke of their territoria, what it had once been, its beauty, its life. This town had once belonged to the villagers. There had once been something here other than dust and heat. The territory had been swallowed by a beast and sat in its belly, disintegrating slowly, its ecosystems turning to ash in the mouths of those who loved it.

We watched from a distance, moved by their solidarity and care. When we left a few hours later, having been guided around the town, we were presented with a small gift: a small piece of ore and miniature carving of a sifting bowl, both dusted with gold. We shook the hands of these brave leaders and thanked them profusely. Then, we were back in the car, grateful to be leaving the dust and the heat, sad for those we had to leave behind.

These defenders were once ordinary people, forced towards bravery because the only other option was defeat. They risk their lives so that their bodies may stand at the foot of these mountains and be one remaining barrier to the power that looms above them, threatening to swallow them whole. Often, heroes don’t have the time to undertake the great odysseys favoured by the Greeks. They can be made in a moment, when they face down the barrel of inevitability and say: Not here. Not today. Even as that beast bears down on them, they remain, repeating: Not here. Not today. The Marmato defence movement are caught in the very belly of the beast and still they say: Not here. Not today.

The beast, in all its arrogance, smirks: If not me, then what?

The defence movement in Tamesis has an answer.

PART 3: The Defence, coming this week.